Journey to Jubilee: From Enslavement to Freedom

What is “Journey to Jubilee”?

Journey to Jubilee dives deeper into the experiences of the Black Americans that were enslaved here at Belle Meade and those that continued to work under labor contracts after the passing of the 13th Amendment. Learn more about the vital presence of the men, women, and children that labored as the backbone of this property. We honor them by telling their stories while continuing our research to provide the full story of what happened here. Using research from primary and secondary sources, this crucial history is explored.

If you are interested in discovering more and experiencing the Journey to Jubilee Tour, click here:

The Beginning of Journey to Jubilee: Reconnecting With History

The “Journey to Jubilee” tour at Belle Meade represents a meticulous effort to delve into the history of American chattel slavery and the role of those who were enslaved, the formerly enslaved, and those in contract labor. This tour, distinct from the Mansion Tour, offers a platform for historians to engage visitors in open discussions about enslavement, utilizing primary sources and oral histories to present a more comprehensive narrative.

Initiated in the 1990s, research into Belle Meade’s history of enslavement involved extensive archival exploration, drawing from documents, ledgers, and personal letters to shed light on the lives and labor of those held in bondage. Despite challenges due to the absence of specific records, ongoing research efforts have aimed to provide a fuller understanding of the site’s history, incorporating local and national perspectives to foster an inclusive dialogue.

It is important to acknowledge the crucial contributions of enslaved individuals to Belle Meade’s prominence as a thoroughbred stud farm, detailing their roles in various industries and craftsmanship. From construction to agriculture, enslaved men, women, and children played integral roles in the estate’s operations, working alongside each other in diverse capacities.

Despite the lack of comprehensive records, efforts are made to honor the experiences of those enslaved at Belle Meade, providing a platform for reflection and connection for visitors and descendants seeking to learn more about their family histories. Our Journey to Jubilee program is an open resource for the public and descendants of the people who were enslaved at Belle Meade. If you would like to share any stories from your family history connected to Belle Meade in particular or Nashville in general or need help with researching your own family’s story, please reach out to our curatorial staff: [email protected].

The tour also highlights the challenges and risks faced by the enslaved, including the threat of violence and the possibility of being sold away from their families. Despite these hardships, individuals seized opportunities for freedom, underscoring their resilience and determination.

However, gaps in the historical record remain, leaving much unknown about the lives of those enslaved at Belle Meade. The tour aims not only to acknowledge their experiences but also to provide a safe space for reflection and connection to these individuals, honoring their legacies and contributing to ongoing conversations about race, history, and memory.

Preserving stories of the past and continuing this research helps us provide quality historical interpretation for the public and an archive of stories that can survive and be shared in the future.

What We Have Learned So Far…

When John Harding purchased land here in 1807, he brought several enslaved individuals with him to work on his new estate which consisted of 250 acres and a cabin on Richland Creek. By 1850, the Hardings were the fourth largest slaveholders in Davidson County with 93 enslaved people, making them among the top 4.5% of slave owning properties in Middle Tennessee. This number increased to 136 individuals according to the 1860 Census. Belle Meade could never have achieved world prominence as a horse nursery and stud without the hard work and talent of the African Americans who labored here – both before and after emancipation.

Over the years Belle Meade grew to include numerous industries and encompass thousands of acres of land. Men who were enslaved primarily worked as farmers, herdsmen, grooms, millers, dairymen, and tanners. Other men were accomplished carpenters and masons. Nearly all of the structures at Belle Meade were constructed using the labor of the enslaved – they built the slave quarters, blacksmith shop, barns, and mills. The 1853 Greek-Revival style Mansion was also completed using primarily enslaved labor. The beauty of their craftsmanship is still admired today.

The enslaved workers also tended to the horses, mules, cows, sheep, pigs, chickens, and cashmere goats. Enslaved women commonly worked alongside the men in the fields plowing, planting, and harvesting the crops. Crops grown at Belle Meade were hay, clover, barley, corn, oats, wheat, potatoes, peas, beans, and apples. In addition to working alongside the men, other women worked as house servants, cooks, nursemaids, seamstresses, laundresses, and dairy maids.

Even young children were expected to work in a slavery-based economy. A child could keep the flies off the dining room table, churn butter, carry wood, and collect eggs. Children were also responsible for polishing the silver and the family’s shoes. By the time they reached the age of twelve, children worked in the fields or began learning a trade, and by age fifteen, they were expected to do the same amount of work as an adult.

Typically, the workday began at dawn, and was signaled by the ringing of the farm bell. There were two common systems of organizing labor on a farm like Belle Meade. One way was the task system, in which enslaved people were allowed time off when the work was done. Otherwise, a farm manager might institute the gang system, meaning the workday lasted until sunset. Different times of the year may require implementation of either system. Contracts indicate that enslaved workers at Belle Meade received Sundays, and possibly every other Saturday, as days off, a concession that likely depended on the season. There is little evidence to indicate methods of discipline at Belle Meade, but the institution of slavery was predicated upon violence and threats as central motivators for work. The Hardings provided direct oversight of their enslaved workers, but they also employed farm managers. Given the proximity of the property to the Natchez Trace, a huge thoroughfare for the interstate slave trade, it is likely some enslaved individuals feared being sold and sent to work on properties farther south, separating them from their family under possibly harsher conditions. Even still, several enslaved individuals escaped the farm in the early years, including Ben, a blacksmith, Ned, Will, and in 1844, a man named James Harding ran away during the Civil War. The risks associated with self-emancipation were high, but the possible dangers did not deter enslaved individuals at Belle Meade. The risk was worth taking in the quest for freedom.

Who Was Enslaved at Belle Meade?

There is still so much that we do not know about the men, women, and children that were enslaved at Belle Meade. For some individuals, we know where they were born, what their lives were like after Emancipation, and when they died. For these individuals, we have not only have a glimpse into their lives but have documented history of the tremendous, systemic injustices they overcame both before and after emancipation. For some of these people we also have a glimpse into their lives: the families they started, the lives they lead, and the legacy they left behind. For other individuals, we may only have a written record of their names once or twice with no additional primary evidence. For many people enslaved at Belle Meade there is no written record. Our mission is to not only acknowledge their experiences but also provide a safe space for reflection and connection to these individuals.

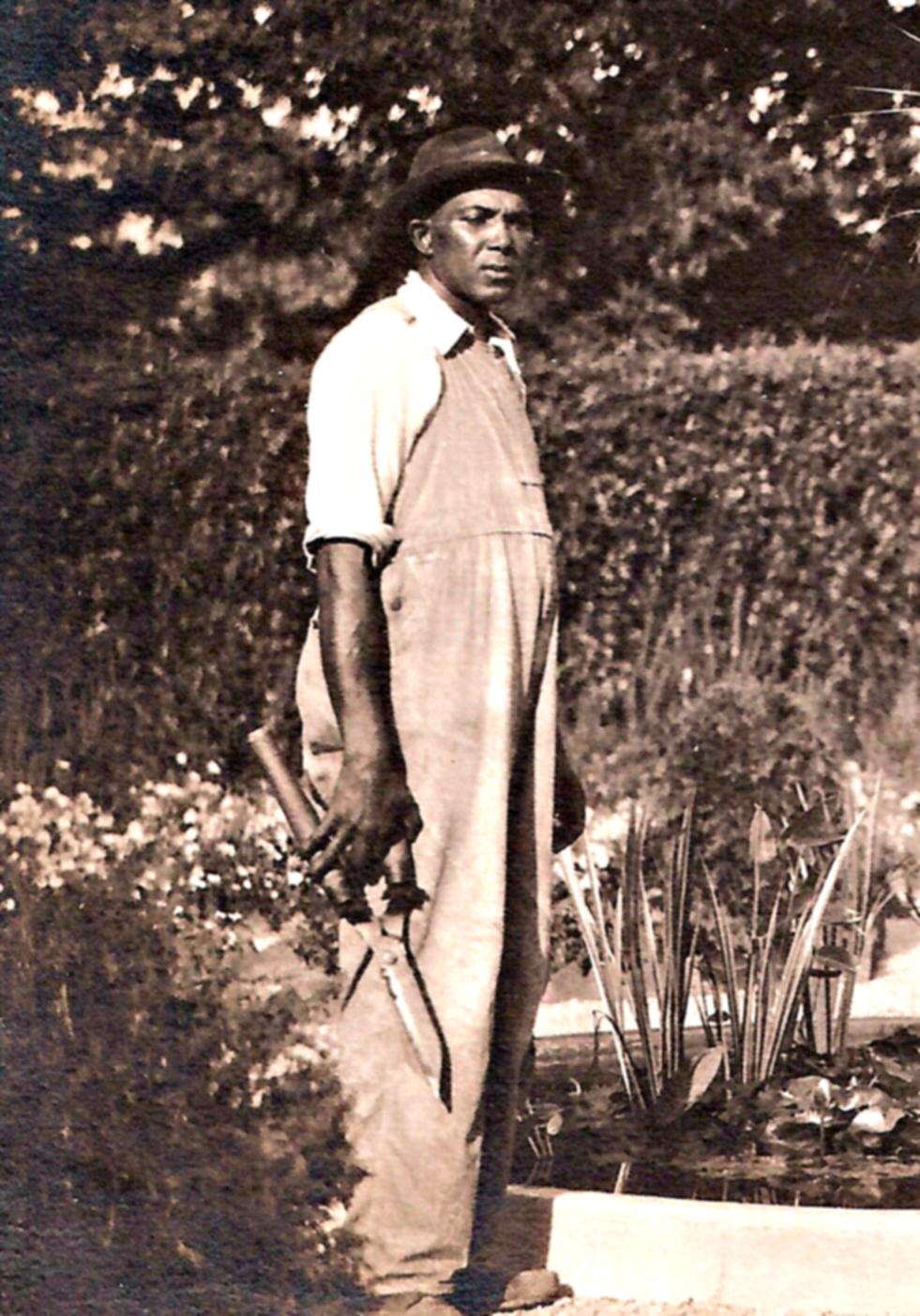

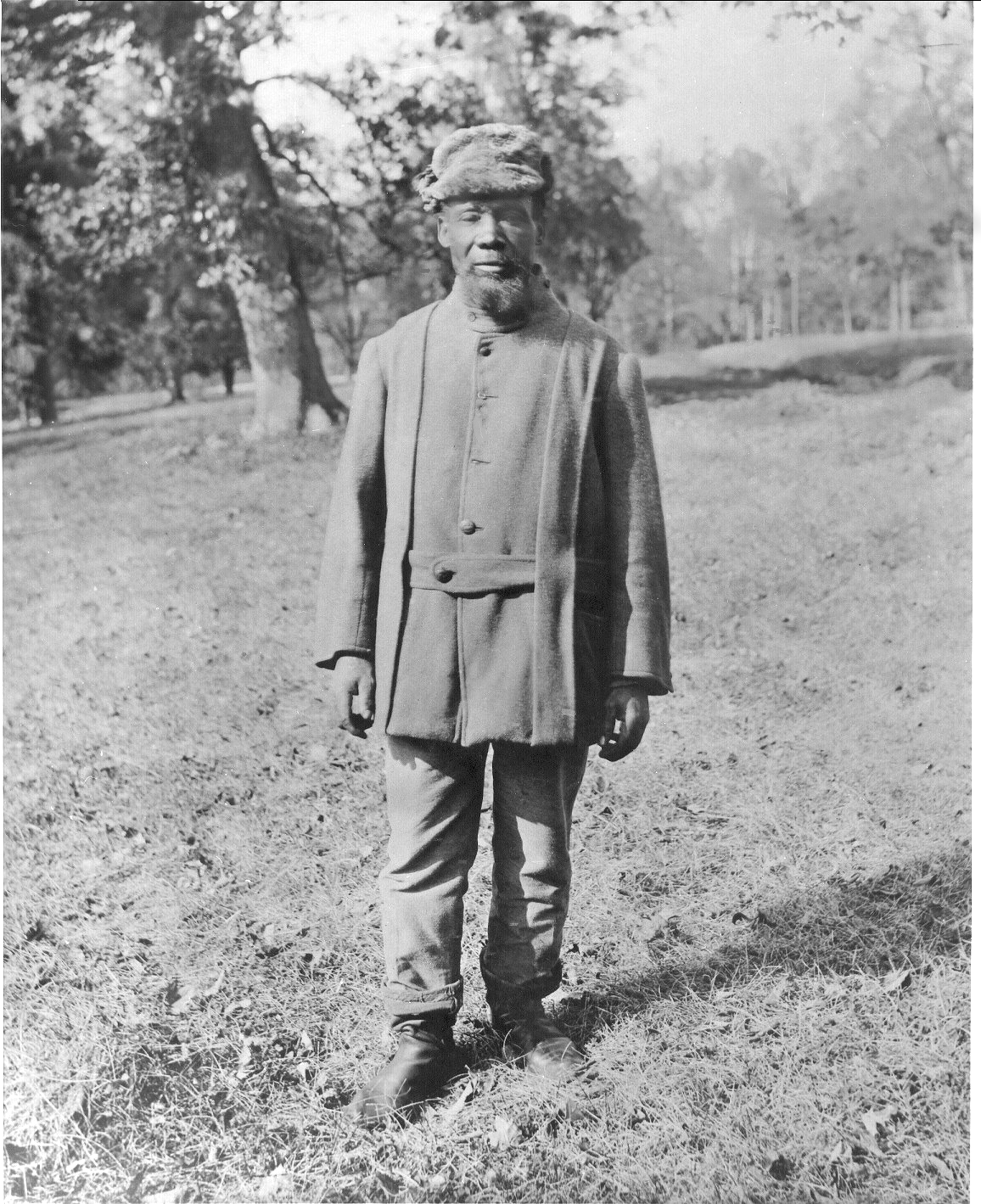

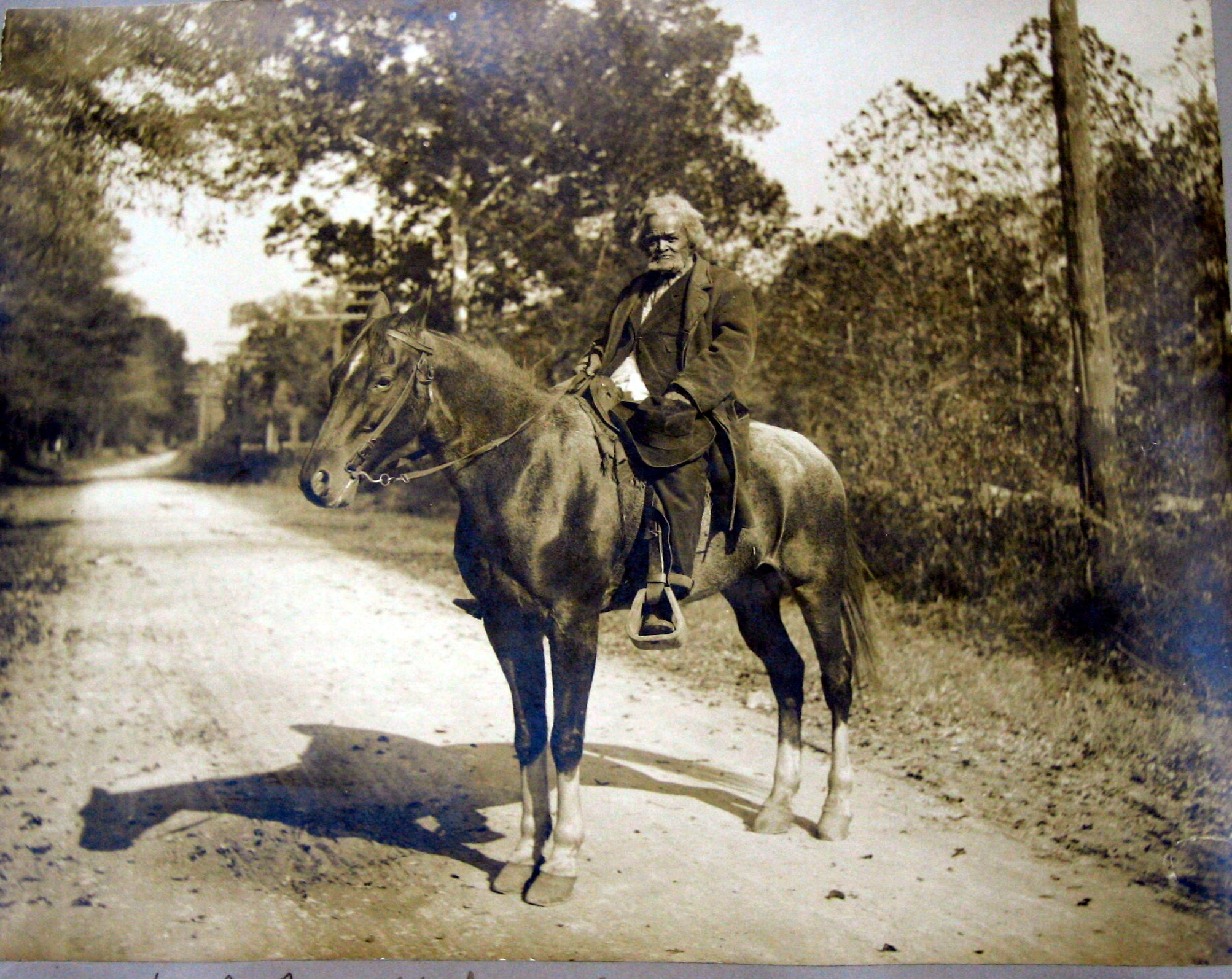

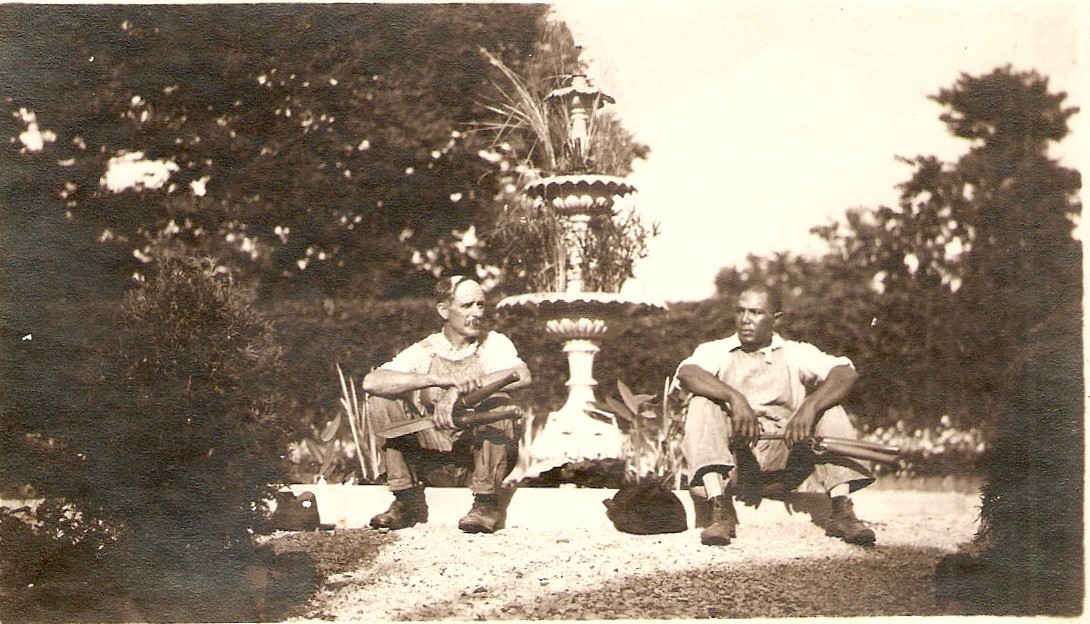

Central to our mission is the commitment to sharing imagery of individuals who were enslaved, formerly enslaved, or engaged in contract labor. Our goal is to highlight their multifaceted humanity beyond the challenges they faced. They held aspirations, dreams, lived full lives, and left behind enduring legacies

We are currently conducting research to discover the lives and legacies of the follwing people.

This list is a compilation of years of research conducted by the staff of Belle Meade as part of an ongoing effort. Sources include the 1860 census, family letters, an 1879 Cash Account Ledger, and the 1879 Farm List.

Many of the duplicate names on this list could be referring to the same person, for example: “Charlotte” and “Charlotte Harding.” We have listed every variation that we have encountered in our endeavor to create the most accurate list possible.

Names in parentheses ( ) refer to the original enslaver selling to the Harding family (according to primary source documents).

Names with asterisks * were found on the 1879 Farm List, which may contain white employees along with African Americans.

Names in italics may be a possible spelling since many of the records were handwritten.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

1835-1917

Alexander Vaulx was born into slavery in Tennessee around 1835, and it is believed that his father’s name was also Alex but his mothers name is unknown. After emancipation, he continued to work at Belle Meade, and according to the 1870 census he was 35 years old, multiracial, and still living on the property working as a carriage driver. He was married to Harriet Vaulx and had two children, Jacob and Milly. In 1872, Alexander bought his own home in cash where the Edgehill Public Library is today. He was self-employed the rest of his life. By 1910 he was widowed and living with his daughter Milly and her family. In January of 1917, Alexander passed and was laid to rest at Mt. Ararat cemetery in Nashville.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

1840-date of death unknown

Harriet Vaulx was formerly enslaved by the Hardings and worked at Belle Meade post emancipation as part of the domestic house staff. According to the 1870 census, Harriet and her family were still living at Belle Meade. In 1872, Harriet’s husband Alex bought his own property for his family where the Edgehill Public Library is today. She would live the rest of her life there. Harriet passed away some time between 1880 and 1900.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

1852-1914

Jacob Vaulx was born into slavery in 1852 to Harriet and Alexander Vaulx. After emancipation he worked as a laborer with his family at Belle Meade. According to the 1870 census record, he was 18 years old. By the 1880 census, he was married to Tennie Vaulx, and they had two children, Henry and Lettie. Sometime between the 1880 and 1900 census records, Jacob learned how to read. By that time, he was working as a foreman at a flour mill and had 3 more children: Morgan, Ella and Bessie. In 1914, at the age of 62, Jacob Vaulx passed away and was buried at Greenwood Cemetery in Nashville.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

1861-1947

Joseph Carter, the son of Susanna and Isaac Carter, was born enslaved in 1861. Joe worked at Belle Meade post emancipation as a personal attendant, ushering guests around the property and attending to their needs. He also worked at Belle Meade when President Grover Cleveland visited in 1887. According to the 1880 census, Joe was able to read and write. Joe married Kate Dungey around 1896, and according to later census records they never had any children. Both he and Kate were working as “house servants” and were living just northeast of Belle Meade. Eventually, Joe and Kate moved to a log cabin on Charlotte Avenue, where Kate’s father had operated a toll road. Joe died in that cabin on February 27, 1947 and was buried at Mt. Ararat Cemetery in Nashville.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

1845-1923

Reuben Harris was born into slavery around 1845 to Richard and Chloe Harris. Little is known about his early life but in the 1870 census, at the age of 25, he was living and working at Belle Meade along with his family. Between 1870 and 1880, Reuben married Francis Harris. The 1880 census records also mentioned that they had a daughter named Gurtie who was 8 years old. The 1900 census showed his occupation as a night watchman at Belle Meade. Reuben passed away in July of 1923 from kidney issues and was laid to rest at Mt. Ararat in Nashville.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

1828 or 1829-1906

In 1829, Robert Green and his mother were enslaved by the McNairy family and given to Mary Selena McNairy and William Giles Harding as a wedding gift. There is little known about his early enslaved life. According to family letters, during the Civil War, Robert was a wagon driver for the Harding family and acted as a bodyguard for Elizabeth McGavock Harding when she traveled. After emancipation, Robert chose to remain at Belle Meade and eventually became head hostler, who managed the care of the thoroughbreds on the farm. That responsibility earned him the highest paid position at $20 a month in 1879 which would equal $610 in 2023.

In 1872, he married Ellen Wadkins, and they had 7 children together. Robert died in 1906 and would be known internationally for his talents in the thoroughbred breeding industry. He was buried on Belle Meade’s property, but unfortunately his exact resting place is currently unknown.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

1829-Date of death unknown

According to oral histories provided by descendants of her family, they believe she and her sisters were born free people because their mother was of Native American descent and were illegally enslaved by the McGavock family when her father passed away. According to McGavock family records Susannah’s parents were Joe and Clara who were enslaved at Carnton. When Selene Harding was six months old, Susanna Carter was willed to Selene by her grandmother, Sarah McGavock. Oral histories from both the Jackson and Carter families tell us that throughout her life, she was responsible for running the domestic side of Belle Meade. Susannah Carter was chronically ill in later life and passed away sometime in the 1890s. The Carter family would continue to hold family reunions until the 1920s. Susannah’s descendents would go on to be a part of major historical events.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.

-

Please check back for more information.