For Use and For Delight

Author: Erica Dahlgren, Director of Interpretation

Grand mansions and elegant grounds have come to be regarded as emblematic of historic sites, like Belle Meade. However, historically, the farm at Belle Meade was fundamentally a place of work, but even still, by the 19th century, families like the Hardings and Jacksons, used the physical setting that they occupied as an expression of their social standing. The layout of the property, especially near the Mansion, was meticulously thought out. At the property’s height, it encompassed 5400 acres of land and numerous outbuildings that all played a specific role to maintain the allure of splendor. Today, the property is just over 32 acres and has only a few of the original buildings left, but these structures can tell us a lot about what life was like at Belle Meade in the past. One of the buildings that is still standing in the backyard is the Gardener’s House/Greenhouse. The original use of this building has been debated over the years, ranging from the first smokehouse, to a spring house, or dairy. However, its location, as well as photographic and archaeological evidence, point to its most logical use as a part of the garden.

Before her death in 1985, author and researcher Ann Leighton wrote, “gardens, from their colonial beginnings, had been blessings as well as necessities, as inevitable as roofs, fences, and wells.” (Leighton, 5) Her words ring true for the Harding family, as their garden was a physical necessity from the very beginning. But, as the family planted the seeds of their success, both social and economic, the garden blossomed into much more than a means of survival. The gardens of Belle Meade set an atmosphere of elegance that drew just as much attention as the Mansion the family called home:

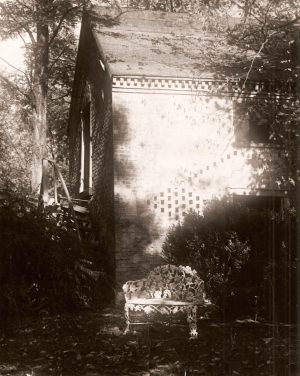

Roses, clematis, coral honeysuckle, and jasmine grew along and over a white [picket] fence that separated the rear of the house from the garden, two ten-foot-wide beds edged with a mat of white spiced pinks. A wide gravel walk separated the beds and extended all the way from the smokehouse to the family vault where blue periwinkle grew on either side of the entrance. In the middle of the walk was a pit greenhouse, causing a break in the garden’s border of nearly twenty-five feet. In the center of the pit was a large box surrounding a mar rosebush (Roses des Maures), its trunk almost as large as a tree. Roses grew “to the top of the pit, twining in and out of a wire netting.” Their blossoms “hung down overhead like a shower of gold.” (Wills, 71)

A Swiss gardener, under the employ of the Harding-Jackson family, breathed new life into the gardens with the addition of botanical rarities that proved to be just as useful as they were beautiful. “There was lavender, bergamot, thyme, heliotrope, rose geranium, musk cluster roses, peonies, tuberoses, lilies, ferns, hyacinths, jonquils, and tulips. Lilies of the valley were not in the garden but could be found in a bed running the entire length of the house. Virtually all the shrubs known at that time, including box plants, old-fashioned sweet Betsy, burning bush, and snowball, were also in the garden.” (Wills, 71) Despite the addition of the more aesthetically pleasing plant life, the garden never lost its functionality; beyond the flower beds was a vegetable garden and an orchard that provided sustenance for the site, while a grape arbor separated the two. Many of these herbs and flowers could be traced to both Carnton and Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage. For example, Sarah McGavock, Elizabeth Harding’s mother, once planted seedlings in her garden at Carnton that were given to her by Rachel Jackson of The Hermitage. Later, Elizabeth introduced those same seedlings into the rich soil at Belle Meade.

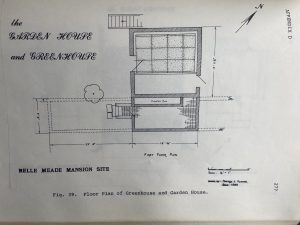

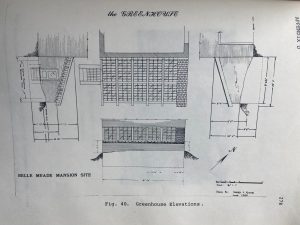

By the 1820s, John Harding was rapidly expanding his Belle Meade property. Various entries in his ledgers show that he was purchasing large amounts of building materials, a fact that supports the idea that he was building new structures on-site. When the Association for the Preservation of Tennessee Antiquities acquired the site in the 1950s, one of the organization’s goals was to determine the age and use of the remaining structures, including the Gardener’s House/Greenhouse. A 1980s study suggests that the building was constructed in the 1820s, a date supported by archival evidence, including Harding’s ledgers. (Kilgore, 32) When determining its use, the building’s location gives a clue: situated between the Mansion and the garden, it was a logical place to store tools and winter vegetables. Sometime before 1850 a “pit-style” greenhouse was butted up against the southwest wall of the Gardener’s House.

That addition to the Gardener’s House at Belle Meade is usually referred to as a greenhouse. The words greenhouse, conservatory, solarium, and sunroom have all been used interchangeably, and their use depends largely on time and place. Greenhouses, like the one at Belle Meade, are typically architecturally simpler but technically more complex. They are designed to help plants survive harsh winters and make it possible to propagate plants year-round. Two major concerns in the construction of a greenhouse are the admission of light and the retention of heat. To meet these needs, the greenhouse at Belle Meade was built partially above ground and partially below ground. Approximately 3’9” is built into the ground to help retain the earth’s heat. The roof is constructed of glass panels that slope from north to south, which allows sunlight from the south to be absorbed by the surrounding brick walls. Belle Meade’s pit-style greenhouse is thought to be one of the earliest of its type in the South. (Wills, 49.) Currently, the greenhouse at Belle Meade is smaller than it was originally. On-site evidence around the existing structure reveals that there was one wing extending in a westwardly direction (towards the smokehouse), and there is a possibility that there was also a wing on the opposite side (towards the mausoleum). The greenhouse at Belle Meade served a specific function for the site, but was also part of the designed route through the ornamental landscape behind the Mansion.

Gardens are living witnesses of the people who made them, tended them, and discovered new plants to add variety and diversity. They are a testament to the extensive knowledge past gardeners had of each species. The garden was curated by the family and cared for by the enslaved workers before emancipation and later, by paid workers. Its purpose was both use and delight. The Gardener’s House/Greenhouse was crucial in the upkeep of the all-important garden.This structure remains today as a testimony to the Harding’s systematic and economical methods, which guided them to eminent success as agriculturalists. Preserving the site’s regional and historical significance today demands dedication to interpreting each part of its history. Each and every building, both past and present, are an integral part of the material culture of this site, and they give us a more personal look at those who lived and labored here.

Wills, Ridley. The History of Belle Meade: Mansion, Plantation, and Stud. Vanderbilt University Press, 1993.

Leighton, Ann. American Gardens of the Nineteenth Century: “for Comfort and Affluence”. University of Massachusetts Press, 1987.

Kilgore, Sherry J. Brief History of the Association for the Preservation of Tennessee Antiquities and Its Belle Meade Mansion Historic Site Museum. 1981.